In an iconic moment from the 2004 cult classic Mean Girls, the naïve and once-sheltered main character Cady Heron learns that even her new high school’s most attractive and popular girls struggle with body image. “I used to think there was just fat and skinny,” Cady muses, but “apparently, there’s a lot of things that can be wrong on your body.”

While the audience is no doubt amused by these young women’s ridiculous self-critiques (“My hairline is so weird!” “I have man shoulders”) the underlying point lands squarely: women tend to identify strongly with their bodies, equating their appearance with their sense of self-worth. And when Cady realizes that she too is expected to offer up a negative self-assessment, we grasp the degree to which women encourage each other to think in this way.

This notion that my body is simply what “I am” runs concurrent to the starkly different—but equally prevalent—view that my body is instead merely something “I have,” no more than an instrument for use or enjoyment. In this essay, I will draw on the work of the philosopher Edith Stein, who suggests that the first perspective is more common in women, while the second is more characteristic of men.

Both perspectives can easily become problematic. The tendency to identify oneself with one’s body can incline women to find self-worth in their physical attributes alone, while men can be tempted to objectify the body by disconnecting it from personal identity. When these views collide, each contributes to a toxic co-dependence between the sexes. As Stein put it, man’s desire for woman as an object of sensual pleasure makes him “a slave of the slave who must satisfy him.” On the woman’s side, her longing for physical affirmation is perhaps best described by the words of Genesis: “Your desire shall be for your husband, and he shall rule over you.” The problem is not simply that the man sees the woman’s body as an object; it is that she struggles to see herself as more than her body.

Both perspectives, taken in isolation, pose significant dangers to human dignity and relationships. But what if we didn’t have to choose? What if the meaning of the body properly included both of these emphases? Stein’s phenomenological writing can help us to identify and integrate the good and healthy dimensions of both characteristically masculine and characteristically feminine attitudes toward the body—and the dangerous distortions that we should reject.

The Body as Instrument

Stein begins from the starting point of the equal dignity of male and female persons, who share a “basic human nature” as images of God. Nonetheless, holding firmly to the Thomistic principle that the soul informs the body, Stein sees bodily differences as more than skin-deep. The distinct physical structures of the masculine and the feminine bodies reveal distinctively commensurated souls, each characterized by a certain “genius,” but also struggling with particular destructive tendencies. Each perspective can broaden and correct the other.

Let’s start with the masculine. As Stein observed, the male body is characterized by size and strength; men tend to be oriented toward and specially “equipped” to act on the world outside them. As she puts it, “With men, the body has more pronouncedly the character of an instrument which serves them in their work and which is accompanied by a certain detachment.”

One reason a man tends to identify less with his body than a woman does is that it is not his body that convinces him that he is a man. Instead, a man tends to identify with his actions, his work, with the accomplishments he achieves through that body. Millennia of cross-cultural initiation rites reveal that young men feel a deep desire to “prove” their manhood through varying feats— whether hunting that deer, winning that debate, or throwing that touchdown. When others recognize and appreciate those accomplishments, a man tends to experience an affirmation of his identity.

Such a perspective is not without risk. Associating oneself with one’s actions and accomplishments can translate into an inability to weather failure, disability, or unemployment. It can also lead to an obsession with material things as “markers” of success—and too often, viewing others, particularly women, as instruments along the way.

But what about the upside? A man’s drive toward accomplishment reminds him that he is, in fact, more than just his body. His physical dimension does not exhaust his identity, but rather enables him to express his spiritual dimension— his powers of intellect and will— in and through his actions.

The Body as Person

By contrast, Stein notes, due to her body’s particular structure— oriented not so much toward “action on the world” outside her but toward the potential to receive and nurture a person within her— a woman tends to experience a closer “connection” or “union” with her body than a man does. She writes, “Woman’s soul is present and lives more intensely in all parts of the body, and it is inwardly affected by that which happens to the body.” Though a bit metaphysically imprecise, Stein’s words express a common experience among women. This feeling among women that somehow “my body is me,” stems from the very particular “maternal” design of the feminine body. Reflecting on the feminine capacity for motherhood, Stein notes,

The mysterious process of the formation of a new creature in the maternal organism represents such an intimate unity of the physical and spiritual that one is well able to understand that this unity imposes itself on the entire nature of woman.

Even without experiencing pregnancy, a woman from an early age receives constant “reminders” from her body’s natural cycles that she is female. Such a close association with her body inclines her to that “identification” illustrated at the start of this article.

In general, women don’t feel the need to prove that they are women. Instead, that sense of identification with the body makes itself felt in the countless occasions when women experience physical imperfections as personal imperfections, and in the nearly universal experience of feeling an emotional thrill when complimented on their appearance. Perhaps it is clearer now why women are more prone to exercise addiction, crash diets, or becoming slaves to fashion. Their innate sense of who they are is wrapped up tightly with the body. And while this close association is fraught with risk for women, we must ask: what is the upside?

Perhaps the biggest one is the fact that when a woman sees a body, she tends also to see a person. Where a man given over to his baser instincts might simply perceive an object for his pleasure or an obstacle to his success, it is quite rare that a woman is not noticing persons. Furthermore, the feminine tendency to see the body as the person also counteracts the masculine emphasis on identifying with success. Often referred to as “mother love,” a woman more easily makes a distinction between who a person is and what he or she does. Because women do not tend to identify with their actions in the way men do, they may be less prone to feeling crushed by their failures, and in fact, are often able to provide that encouraging sympathy which can bring others back on their feet again.

Uniting Being and Doing: The Power of Symbol

Both characteristically masculine and feminine approaches to the body reveal key truths. Women tend to be more instinctively aware that the body is an essential aspect of personhood; men more intuitively sense that the person is more than his or her body. By sensing that her body “is” her, a woman highlights the body’s capacity to represent, to “show,” the person. By sensing the body’s instrumental quality, men remind us that the body is designed to “do” something.

These aspects of “being” and “doing” are brought together in the concept of symbol. Translated from the Greek word meaning “to throw together,” a symbol incorporates both aspects of being and doing. A symbol both represents and connects. It shows what something is, and then functions to connect persons in understanding it. Why would anyone paint a picture, fly a flag, or speak a word unless he expected other persons to see or hear it, to be brought to some understanding through it?

Josef Pieper reflected on this twofold meaning when considering the symbolic nature of words. As he put it, “words convey reality. We speak in order to name and identify something that is real, to identify it for someone, of course—and this points to the second aspect in question, the interpersonal character of human speech.”

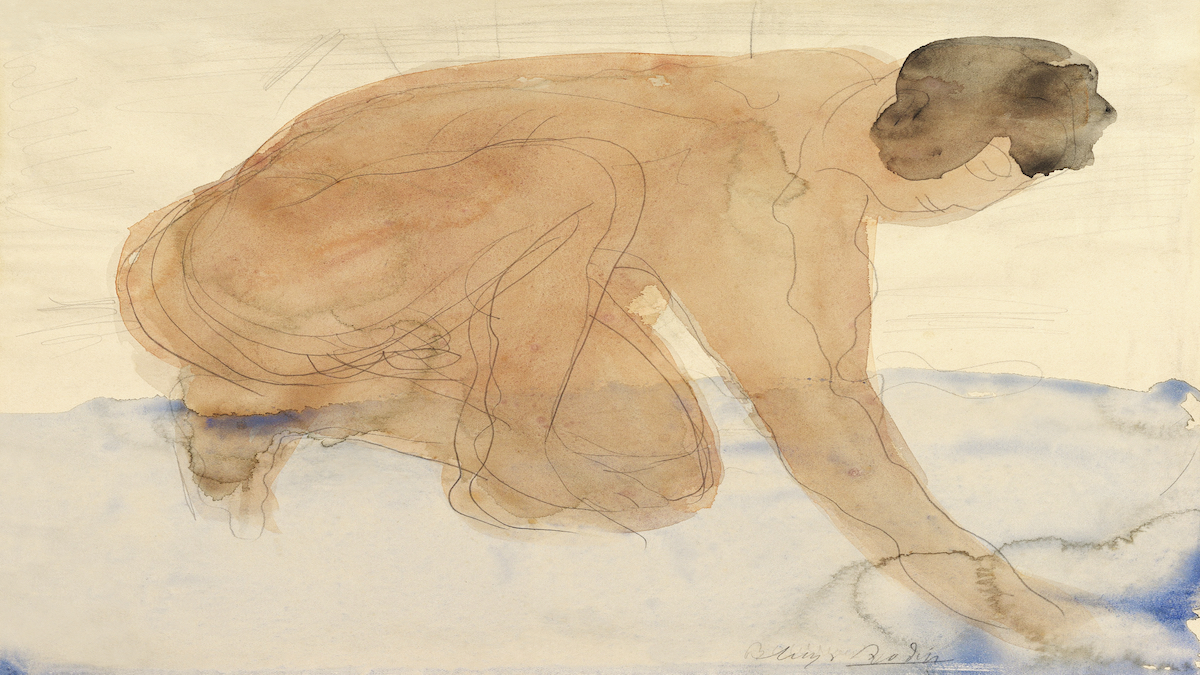

In a way analogous to a word that is spoken, the body itself both represents a reality and connects it to others. Manifesting the person, the body serves as a symbol par excellence. It “presents” a reality—the whole of which is not entirely material—in a visible way.

But like all symbols, the body does not only show but also connects. One person is able to know another, to relate to another, only through that bodily medium. It is not an either/or proposition. The body is both representative and instrumental. The body “is” something, just as it “does” something.

At their weakest, men think of sex as sport—merely something pleasurable to do—and forget that they are connecting to a person. Women, at their weakest, are tempted to consider themselves as purely ornamental, with nothing to offer except an attractive physique. Meditating on the healthy aspects that each perspective has to offer, however, can assist each sex in its struggle to avoid such degrading extremes. Such assistance is most deeply effective within the family, when a child is able to consistently experience the complementary aspects of symbolic reality reflected through the union of a mother and a father, and through his or her individual relationships with them both.

Remembering What the Female Body Can Do

When it comes to the perennial struggle with body image issues, young women like Cady would do well to consider the instrumental function specific to their bodies. The female body is not just something to look at! It has the capacity to do something both unique and amazing.

The modern oversexualization of women’s bodies goes hand-in-hand with a diminishing awareness of their distinctive biological function. Our culture treats a woman’s natural fertility as a disease. Not only is her potential motherhood often ignored, but it is actively subverted and destroyed. What more powerful way to compound the notion that a woman’s body is purely for display! The very idea that the female body is oriented to supporting and nurturing another person is a key to understanding the body in general. The beauty and fitness of our bodies aid our relationships. They are not meant to turn in on themselves, but to bring us out of ourselves in service of human communion. As Everybody Loves Raymond’s Debra Barone once put it, “I’ve had three kids, you know? These are not just for show. These were working breasts!”

This powerful truth hit me as a young mother. Though I knew intellectually that my body had done something powerful in bringing my babies to term, I still struggled to see myself as more than that somewhat worse-for-the-wear instrument. After my fourth child, I struggled to lose the baby weight and began an exercise program. Initially only doing it so that I could fit back into my “skinny” clothes and feel “pretty” again, I was delighted to find that my new energy level helped me to become more adventurous and physically active with my older children. There it was again: my body was not simply “me.” It was enabling me to go beyond myself—to connect with my loved ones and experience the joy of nurturing their growth. Without that reminder of what my body can do, I could have all too easily lost perspective on its symbolic character. I began to marvel more and more at the gift it is to be able to bear a child in the first place!

By the time I gave birth to my seventh at age forty, my appreciation of my body as an instrument deepened again. I suffered from a pregnancy-induced back injury and could barely get around for months. I longed to be able to do the things I needed to do for my family—for a functioning body that could vacuum, drive, and cook meals without back spasms. As my health slowly returned, I told myself I would never forget that my body is an amazing instrument which serves me in all of the relationships in which I find my fulfillment. I strive to keep that perspective in my approach to its care.

Our culture today is swimming in the mess resulting from two incomplete understandings of the body interacting at random. The transgender movement, for example, is tangled with threads of both the feminine body-as-identity view and the masculine body-as-instrument view. But such views easily devolve into harmful caricatures if not balanced with the larger truth of the body’s symbolic nature. It is only when men and women share their complementary perspectives on the body with one another that each can appreciate the fullness of its meaning.