From education, to employment, to family formation, younger men are disproportionately failing to thrive in today’s America.

Although conservatives were the first to sound the alarm, figures across the political spectrum are increasingly concerned with men’s plight. Why, progressive New York Times journalist Ezra Klein asks, is it so hard to conjure a positive model for manhood in the twenty-first century? Brookings Institute scholar Richard Reeves has devoted a full book, Of Boys and Men, to the problem.

Some on the right—GOP lawmakers like Josh Hawley, complicated cultural figures like Jordan Peterson, and misogynistic influencers like Andrew Tate, to name just a few— blame progressives’ attack on “toxic masculinity” for the alleged “decline” or “deconstruction” of “manhood” among boys and men. But if we are going to get to the source of our current ills, we must first resist framing as the de-masculinization of men what is in fact the infantilization (or, de-adultification, if you will) of all Americans—male and female alike. The issue is not one of sex, but of human maturation—or the lack thereof.

An expectation of physical and psychological fragility dominates the mainstream vision of American childhood today. This does boys and men no favors. But it hurts young women too. Rather than seeking to cultivate a character of perseverance in the face of emotional, logistical, or intellectual difficulty, parents and teachers increasingly teach both boys and girls to expect convenience and to seek comfort.

Growing from a boy into a man is a universal male experience of physical maturation. A woman is quite simply an “adult human female,” and a man is equally simply an “adult human male.” Such a definition of manhood is morally neutral: war heroes are usually men, but so are violent criminals. What makes the former different from the latter is not his masculinity. It is his character.

Making both men and women more like small children is at the core of today’s veneration of fragility and marginalization of grit. Making men less masculine has nothing to do with it.

Our Infantilizing Culture

In an article titled “Why We Need the Patriarchy,” Nina Power convincingly argues that contra contemporary feminist zeitgeist, we do not live in a patriarchy where men would be expected to “tak[e] responsibility for their families and for society at large,” but rather in “an infantilized culture in which men and women are more like brother and sister, contending against each other in a condition of perverse equality.” The equality in question is perverse, in my view, because many parents and schools unintentionally perpetuate both boys’ and girls’ immaturity through coddling, rather than fostering their maturity through the development of physical, emotional, and intellectual resilience.

As Greg Lukianoff and Jonathan Haidt argue in The Coddling of the American Mind, we are presently delaying children’s opportunities for solo problem-solving in the real world until several years too late. Instead of building our children’s confidence by allowing them to, say, walk home alone or buy something at the store unaccompanied, we behave as though danger that is beyond their capacity to manage lurks around every corner—and the kids believe us. As a result, 18-year-olds today are, Jean Twenge writes in iGen, “like 14-year-olds in previous generations.”

Moreover, today’s infantilization of kids is emotional and intellectual—not just physical. So-called “gentle parenting,” which centers children’s emotions rather than their behaviors, has become an aspirational norm. Meanwhile, broad reduction in academic rigor is ushered into schools under the banner of “inclusion.” And in many places (including some girls’ sports), the feelings-based trend of transgender identification trumps sexually dimorphic biological fact. We are—often with the kindest of intentions but heedless of the unintended consequences—rendering today’s young Americans and the country that they will inherit increasingly fragile.

Are Women More Fragile Than Men?

Women, on average, may be more susceptible than men to an inculcation in the fragility discussed above. But it does not follow that women are therefore naturally fragile. The fact that a person is more apt to be harmed by a negative phenomenon does not make identification with that phenomenon innate to her character. Using “masculine” as though it is a synonym for “adult” implicitly equates what is feminine with what is infantile.

The mental health crisis among teenagers is concentrated among females who identify as progressive. In other words, it is most pronounced among girls who believe that insulation from political perspectives with which one disagrees and adherence to one’s preferred pronouns are important components of one’s basic safety. These are infantile ideas—and women are indeed more susceptible to embracing them than men. That’s likely because, on average, women are both more agreeable and more neurotic than men. So, when someone claims to feel “triggered” by words in a classic novel or experiences gender dysphoria, more women than men are likely to experience empathy for the person in question, as well as to project negatively on the presumed agent of that person’s affliction.

This is not a bad thing. People who are naturally empathetic, whether male or female, have valuable strengths to offer society. But empathy unchecked by the discipline of truth is like aggression unchecked by the discipline of order: it renders people unfit for either personal or political self-governance.

Indeed, to the extent that girls are out-performing boys in American schools today, it may be, in part, because more girls are comfortable in a world where Tracy Hoexter’s The Wrinkled Heart (2015), is commonly considered formational literary fare. In this story, a young boy is so deeply impacted by his mother’s impatience and two classmates’ unkind words that his heart is permanently “wrinkled.” The story fosters children’s natural emotional solipsism rather than inculcating resilience. Girls’ mental health concerns notwithstanding, more females than males may succeed academically and culturally in an environment where this kind of unhelpful fragility is not only accepted but encouraged.

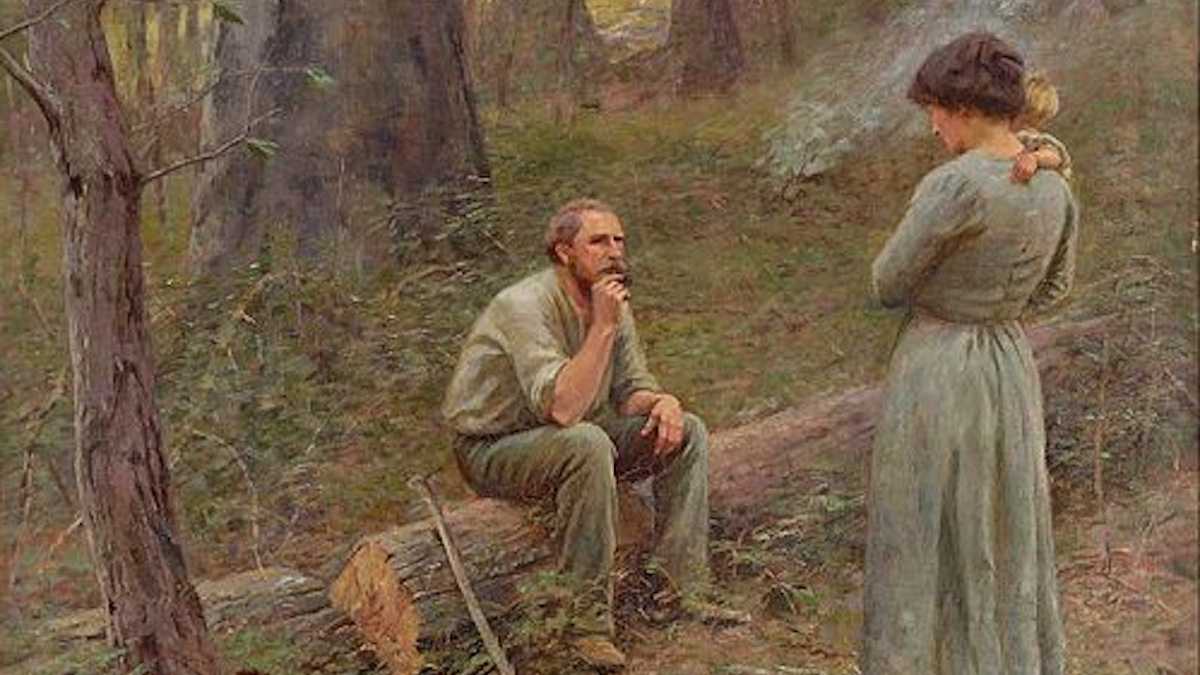

Meanwhile, more boys than girls will fall through the cracks in less than subtle ways. As they age, the young men who fail to thrive in our current educational and professional climate often react by embracing a characteristically masculine version of infantile existence: wallowing in the kind of Peter Pan-dom that makes them unsuitable partners for adult women. This is what those concerned about the present crisis among American men are picking up on.

Reason, Courage, and Strength of Character—For Both Men and Women

Conservatives acknowledge—and rightly criticize those progressives who fail to recognize—that men’s greater average propensity toward aggression is not a flaw, but a biological reality. Any society that aspires to safe and peaceable living must virtuously direct, coercively control, or (most often) impose some combination of formation and coercion to manage this tendency. Men should not be accused of “toxic masculinity” simply for being less agreeable and more aggressive than the average woman.

If we blame the personal and psychological fragility that has become a norm among too many men on a decline in “masculinity” (rather than on the failure of too many men to embrace responsible adulthood), we risk implying that such fragility is somehow constitutive of womanhood. Women’s physical differences from men are incontestably real, and our capacity to bear children does make us more vulnerable in important ways. Yet the implicit assumption that these differences make us emotionally fragile and easily “triggered” is a self-fulfilling prophecy. Indeed, it makes women even more susceptible to the direst effects of America’s new culture of infantile fragility.

Moreover, chalking males’ problems up to a failure of “masculinity” doesn’t just discount the developmental needs of girls and women. By focusing on the decline of “masculinity” rather than the development of character, it also fails boys and men. For while fathers today are far more involved with their children than those in the recent past, it remains true that children—boys as well as girls—are formed in many ways by women. And boys—like girls—will continue to languish in a culture that infantilizes them unless their mothers, fathers, teachers, and coaches reject that culture wholesale, reestablishing the expectation of resilience over that of fragility for both sexes.

Women are capable of the same moral growth and accountability that those who praise the “masculine virtues” seek to reestablish as a norm for men. All adults, regardless of sex, should aspire to emotional and intellectual strength. What’s more, working to reestablish this norm for both men and women is a project in line with the best of our American heritage.

In the 1840s, the French philosopher Alexis de Tocqueville argued that Americans’ great capacity for innovation and industry was mostly due to “the superiority of their women.” Tocqueville saw American women as unique embodiments of exactly the reason, courage, and strength that conservatives like Hawley are attempting to reinvigorate in American men. While these virtues are often exhibited differently by females than by males, contemporary American women must exemplify them—no less than our brothers today or our foremothers in the nineteenth century—for the benefit of men and women alike, if our society is to thrive.