“I took a pregnancy test and it was positive… everything, all my manlihood that I’ve worked hard for, for so long, just completely felt like it was erased.”

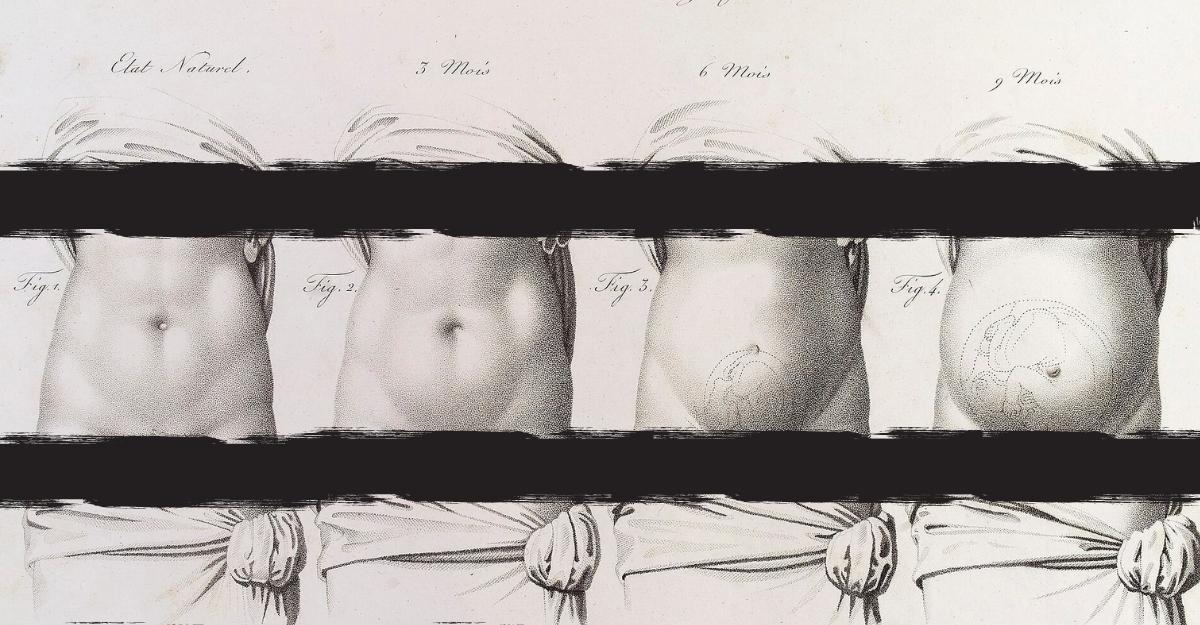

This year, the cover story for British Glamour’s “Pride Month” edition is an interview with Logan Brown, a trans-identifying woman who has undergone hormone replacement therapy and a double mastectomy in order to appear as a man for the better part of her twenties. One day last year, having been off of her prescription testosterone for a while due to some health issues, she joined the ranks of countless other women who have been surprised by an unexpected pregnancy—and who, despite some ambivalence, chose life.

The interview, headlined “I’m a pregnant trans man and I do exist,” checks all the familiar boxes of the type of agitprop the world has grown accustomed to seeing in the month of June. Stilted, redundant, irrefutable claims about one’s own “existence” as a queer person: check. A victimhood narrative involving the “hate speech” of conservative commentators: check. An announcement of a forthcoming children’s book on the “fluidity” of gender: check.

Despite the interviewer’s formulaic flattery, moments of radical honesty—and of deep maternal sentiment—shine through. Answering the question of how she overcame her anxieties about pregnancy, Brown answers, “I realized I didn’t want the thought of having to get rid of the baby when it was happening inside my body; it was a really, really weird feeling.” For the courage it took to lean into that really, really weird feeling, the deep, exclusively female, embodied knowledge that life blooms in your womb, Brown should only be applauded.

However, Brown reflexively shrinks from the aspects of motherhood that required real bravery, verbally stumbling and redirecting to some prefabricated claim about “queerness” whenever issues related to her inescapably female biology emerge. Rather than elaborating on the harrowing experience of laboring for days, then giving birth via emergency cesarean, then remaining in the hospital for a week with an infection, Brown responds to questions about her birthing experience by recalling being misgendered by one of the very physicians who saved her life: “I remember being in the C-section and one of the doctors referred to me as ‘she’, and someone else corrected them and said ‘he’. I did get called ‘she’ a few times though.”

To skirt the profound suffering of childbirth in favor of a gripe about language, as if misgendering is the true cross to bear while your uterus is being sliced open, illustrates the constant state of denial at the heart of transgender ideology. Transgender “healthcare” is a process of consistently treating emotional symptoms of trauma as wellsprings of identitarian insight (and profit potential). In puberty, when she had her breasts removed, and now, after having her body disassembled as only a mother’s can be, Brown’s fixation on perfect ideological purity is meant to distract from the bloody reality. In all cases, it amounts to just another form of escapism.

When her journey began, Brown admits, she was a young teenager with profound mental health issues stemming from sexual confusion. She came out as a lesbian, but viscerally hated her breasts. Later in life, after the internet taught her how to recite the magic words (“I’m transgender”), she began the journey of “transitioning,” which would supposedly close the gap between her gender identity and her sex. By making the latter conform to the former, it is suggested, transgender people can overcome their sadness. Despite its demonstrable falsity, this lie remains the foundational assumption of what is euphemistically known as “transgender healthcare.”

Brown, like most of her trans-identifying peers, has been diagnosed with other mental problems. She laments that NHS staff members were insufficiently accommodating not only of her preferred pronouns but also of her emotional difficulties. “Being pregnant, in general, is really, really difficult. Then add me being trans… I would have liked some mental health support. Some midwives get it and some midwives don’t. I feel like with LGBTQIA+, it shouldn’t be optional for them [NHS staff] to have that sort of training. It should be mandatory, because we do exist and people are going in there.”

Tragic irony and self-contradiction run throughout the feature essay. But most tragic, ironic, and self-contradictory of all is the letter Brown wrote to her newborn daughter, Nova, the text of which Glamour published in full. In the interview, Brown repeatedly insists on the distinction between sex and gender, emphasizing that they “are completely different things.” She also explicitly states that being a woman is “horrible.” Yet Brown doesn’t hesitate to “assign” her child a “female gender identity.” In other words, she does to her daughter exactly what she claims caused her own debilitating mental health disorders.

Brown doesn’t seem to understand the subtext of her own words, and this is part of what casts doubt over the entire project. How did the people who decided what would be on the cover of Glamour UK, one of the biggest magazines in the world, arrive at an obscure transgender TikToker, with not even 4000 followers, who struggles to tie together a coherent thought extemporaneously or in writing? Why would a magazine that purports to support people like her dress this openly mentally ill person in such cheap clickbait, literally painting a man’s suit onto her pregnant belly and mutilated chest, parading her all over the internet like a lamb to the slaughter?

This isn’t simply activism disguised as journalism. It is cruelty disguised as “care,” exploitation as exaltation. Sadly, it appears this is the only internal consistency the transgender movement can claim.