In January of this year, I got an innocuous email from Chicago Public Schools with the subject line “Personal Health & Safety Education Notification.” I opened the email to find a list of links to information about sex education curriculum that would be taught to my fifth- and second-grade daughters in the coming weeks. I clicked on the link to the public list of topic areas.

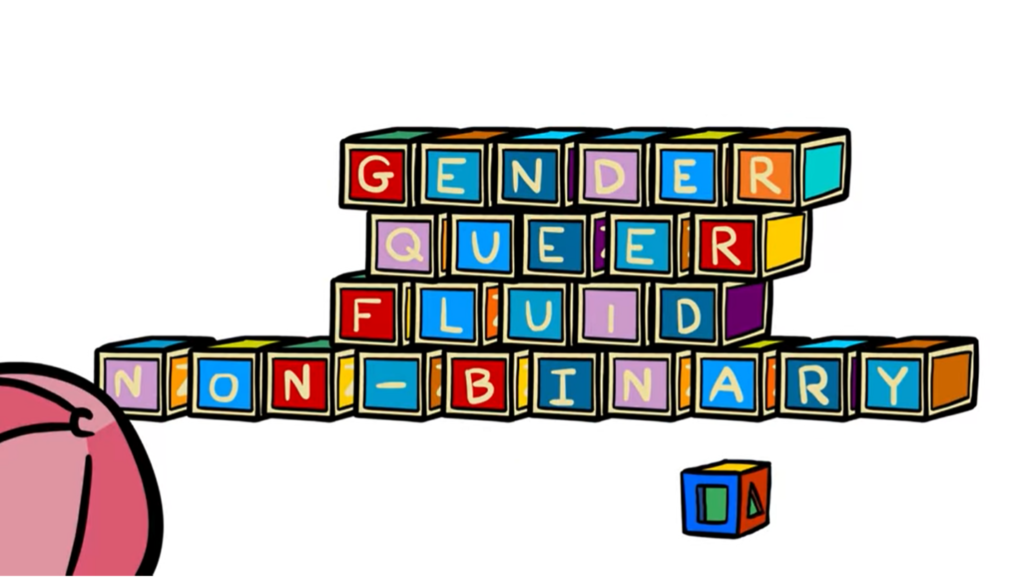

I pored through the information for my daughters’ grades. There are lessons on sexual attraction, wet dreams, the “safety” of puberty blockers, the anatomy of intersex individuals, artificial insemination and in-vitro fertilization, and a variety of sexual orientations and gender identities including “gender queer, fluid, and non-binary.” There are lessons for young elementary students with anatomical drawings labeled: penis, scrotum, anus, vagina, clitoris. Students are taught that “male” and “female” are not innate biological aspects of a person’s identity, but arbitrary descriptions assigned to babies at birth.

My heart sank.

From Chicago to Uruguay… and Back Again

Only a couple months ago, we moved back to my hometown of Chicago after seven years in Uruguay, a quiet little country nestled in between Argentina and Brazil. My husband and I and our two (now three) daughters ran off in 2016 due to a number of fears. I worried about raising my girls in a city, with little connection to nature and no understanding of how food is grown. Back then, I wasn’t worried about puberty blockers; I was worried about Adderall. I was worried about the effects of insufficient recess and lunch times, the long hours of industrial schooling forcing them to sit still, and the epidemic of students being medicated into doing so. I wanted a slower life. We wanted to homestead and to learn another language and to give them the softest and sweetest childhood imaginable, picking mulberries in the afternoon and running in the fields with free-range chickens underfoot.

We did that for seven years, and it was magical. We raised our three girls from infancy to childhood in this sweet place, with wonderful neighbors, a lovely climate, and very little worry that our kids would be actively harmed by their little rural school. But as my eldest started to move out of the earliest elementary grades, we started to see the limitations of our plans. As adolescence approached, she started to feel the strain of being culturally different—an American amongst Uruguayans. With the more complex feelings of adolescence, came a difficulty to express her thoughts and feelings in her second language of Spanish. Friendships that were once easy started to become strained and complicated. Academically, school beyond the primary years also proved to be lacking. She was falling behind, and we weren’t able to catch her up quickly enough.

What’s more, some of our fears about life in Chicago and the bad influence of American social justice ideology were making it to our tiny town in Uruguay. Right before we left, we noticed our friends’ pre-teen daughter and her friend group were all experimenting with various forms of queer identities, and my eldest daughter got into a fight with a friend about whether or not “skin-colored” crayons were “racist.” Apparently, nowhere is safe from what’s coming.

In the meantime, while my husband and I were in Uruguay, our siblings began having children. Those cousins started to grow up and form bonds with my girls every time we came for a visit to Chicago. In late 2023, we made the decision to go home and re-embrace our families and our neighborhood. We even decided to enroll our girls in the institutional behemoth that is Chicago Public Schools.

With this email, only a few months into my daughters’ time at the school, all my fears came to the fore. Was this the right choice for my family? Am I going to harm my daughters irreparably by letting them be exposed to peers steeped in this ideology? And most importantly, What do I do now?

Before we left for the United States, I began to talk to my two older girls about some things to expect in Chicago. I told them that there are more or less three different harmful philosophies that they could expect to encounter: 1. That you in particular, a child, should feel guilty or responsible for the abstract concept of racism, even though you are not racist, 2. That the climate and environment is in such a dire condition that we will all surely die within our lifetimes from environmental calamity, and 3. That it is common to feel like you a born in a body whose sex doesn’t match your actual, “true gender.”

Each of these points required detailed and careful unpacking to address the valid concerns of ongoing and historic racism, environmental degradation, and hateful acts toward homosexuals. I am not afraid to admit that these social issues are absolutely real. As a trained environmental sociologist, I certainly believe there are real problems that adults and children should acknowledge and work to correct, in constructive ways. What’s particularly insidious about the most extreme ideologies is how they hijack the desire to be tolerant, active citizens engaging with real social issues, turning this good desire into something unhealthy, authoritarian, and detached from reality.

Before we even arrived in Chicago, I knew that my primary goal was to maintain the lines of communication with my children. I would let them be exposed to this thinking, which is now shockingly ubiquitous, to help them separate truth from fiction. So I told them: Yes, a certain percentage of the population is gay and lesbian, and it is good to be tolerant of that. No, it is not common or normal to feel like you were born in the wrong body and need medicine or surgery to fix that problem.

At the Cutting Edge

After scouring of the materials (or, at least, the links they allow parents to see), I found the vendor the Chicago Public School District uses for their curriculum videos. I began to watch through the assigned videos and more, leaving some open to show my husband and discuss with him later in the evening.

At the bottom of the first email communication there was a link to a form that parents can choose to opt out. At the end of the day, when my husband and I had time to discuss privately, we watched through several videos, I shared with him the highlights of my concerns, and we decided to opt both of our girls out of this curriculum altogether.

While I was glad for the opportunity to opt out, I began to feel shaky and unsure. Part of my goal in moving back to Chicago is to not cede what could be thriving institutions like public schools to the most extreme and cynical actors. But I felt overwhelmed and scared. How many parents have the time and inclination to go through this curriculum in the way I just did? Do people even know what is being taught? And what about my daughters? What if I can’t do enough, quickly enough? What if our influence as a family isn’t strong enough to overcome social and peer pressure?

A couple of weeks later, I received an email from the sex educator about my eldest daughter’s first lesson in health education. I was told that she would be bringing home a worksheet to work on at home. It turns out the form I filled out never made it to the teacher in charge of sex ed, and my daughter was involved in the first lesson. Luckily, this first lesson was innocuous—even positive. It was about general self-image: characteristics you like about yourself and places where you feel you could use some improvement. This particular lesson is one I think could and should be in health education classes.

I immediately emailed the sex ed teacher to make sure she had received the form opting both of my girls out of these lessons. She apologized, reassured me that my daughters would not be involved in future lessons, and offered to meet with me and my husband to answer any questions we had on the curriculum.

We set a time to meet.

I planned to tell the teacher that I had some general misgivings about the curriculum, but that I wanted to know about the content so that I could teach my daughters these concepts at home, because I know my daughters’ maturity levels best. At our meeting, the teacher began to go through the curriculum. She immediately indicated her own misgivings about some of the concepts, and her doubts about whether or not the children were ready to be exposed to some of the more explicit ideas.

As we went through the curriculum, it became clear that much of the most objectionable content—advocating for puberty blockers, the focus on intersex bodies, etc.—was new this year. This was the first time she was seeing some of it.

I thought: we are really at the cutting edge here, aren’t we? How many people even know the details of this curriculum, which will be taught to over 300,000 children this year? Who is pushing this curriculum that is so out of step with what educators and parents think kids should be learning?

Reason for Hope—And Vigilance

After going through the curriculum and hearing the educator’s misgivings, I felt reassured. It seems that an ideologically captured vendor has created and sold a curriculum that is vastly out of step with what most parents, children, and even teachers are comfortable with—or would be comfortable with, if we had the time to find out what was being taught. All of us are stuck in the tacky abyss of mandates and bureaucracy, just struggling to navigate modern life. I started to feel a kinship with the sex ed teacher. She was plopped down into the morass, just as I was. She is doing her best to do right by her students, to pull out the good and helpful from the absurd and ideological.

This newfound camaraderie does not mean I will be letting my children take the class, but it does give me a kind of hope. The hope is not based in any expectation that things will reverse quickly or without a fight. Instead, it’s based on the fact that so many of us are still holding onto a sense of normalcy, in the sociological sense, of the norm, and it’s not “queer gender fluid nonbinary.”

In general, I don’t like to publicly share personal stories involving my children. But after this experience, I feel that I must implore other parents to pay attention. Use your agency where you can. Show up.

We cannot object to the secret and quick advancement of ideas we don’t agree with if we don’t engage. I am not only worried about my daughters, but the three hundred thousand children who may not have advocates at home making sure they separate helpful truths from harmful fictions, and the hundreds of thousands more in school districts across the nation who are being taught to equate health with harm.

Since that meeting, I have used three approaches to push back on what I learned.

First, I am writing this article, even if it is out of my comfort zone and may result in some awkward pushback from my local school or Chicago Public Schools administration. I think it’s important to use my voice to draw attention to what is being taught, and to let other parents make an informed decision.

Second, I am having conversations with other parents involved in CPS. I am bringing the explicit aspects of this curriculum to their attention and asking them to look into it further. Some of these parents are networked into local school councils and PTAs and hold various leadership positions across CPS. My hope is that the network effects of this information will make a difference.

Finally, I am taking an active role educating my daughters. I am finding out what their peers are being taught and explaining the concepts to them in a way they can understand and a way that aligns with our family’s morals.

We live in an era when we simply cannot trust institutions to share our values. We must use our agency as parents to take an active role in our children’s lives, their educations, and the institutions of which we are a part. I strongly believe that these institutions—schools, churches, civic organizations, and more—are worth saving. But if all the conscientious parents opt out, they will be ceded to a set of actors whose vision of a good life and a healthy society may be very, very different from your own.

This is what local politics looks like. Show up, pay attention, let your voice be heard, and advocate for the less powerful, especially children. The children in these schools will be your children’s peers, now and in the future. It is our responsibility to breathe life into the institutions that form them, and to mold them to reflect our civic values. Don’t give up!