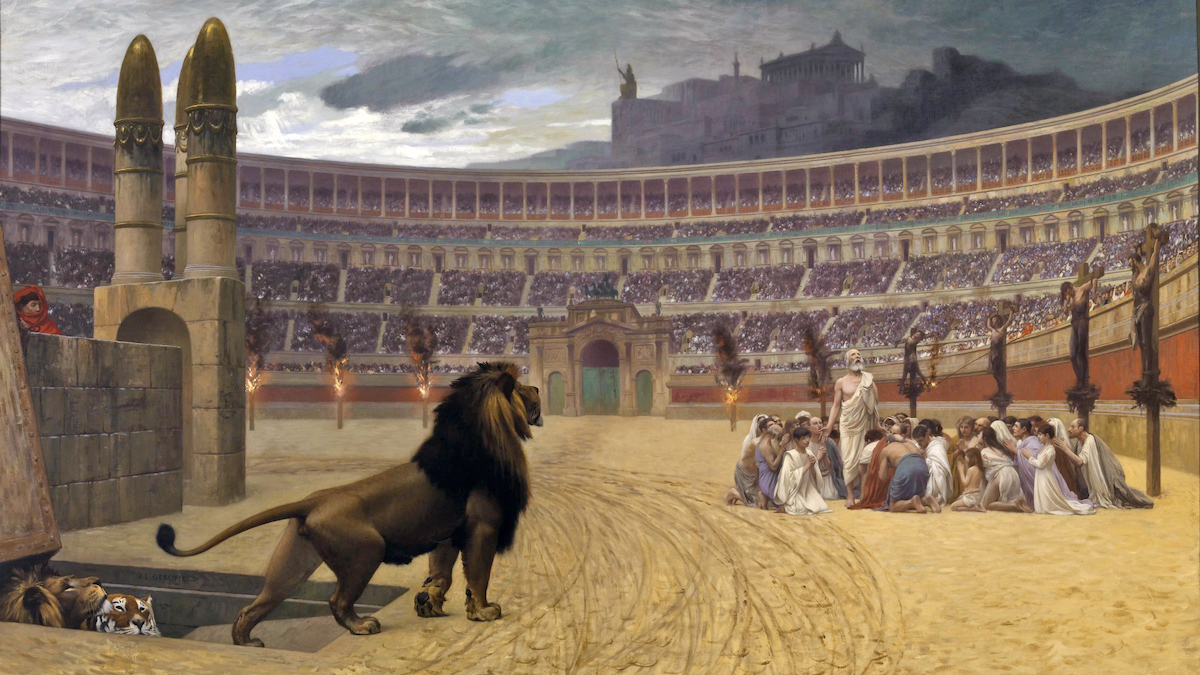

On a sunny spring day in 203 CE, in the city of Carthage in the Roman province of Africa, thousands of people crammed into the magnificent Roman amphitheater, jostling each other for the best seats, eagerly awaiting state-sponsored entertainment that was one of the perks of living in the Roman Empire.

Trained gladiators were highly expensive, as were the exotic animals they regularly fought. Roman officials, therefore, regularly supplemented the immensely popular gladiatorial games with condemned criminals. That day, however, the condemned criminals in question were not the usual murderers and highway robbers.

This time, they were Christians—female Christians.

We know their story because one of their number, a young noblewoman and nursing mother, kept a journal of the events and her visions while awaiting execution in prison. Following her death, someone preserved her journal, added his own description of the execution, and published the account along with a shorter journal entry from another martyr executed that day. This “Passion of the Martyrs Perpetua and Felicity” became an early Christian bestseller. It also has the honor of being the earliest Christian account written (mostly) by a woman.

Both the content of Perpetua’s journal and the sheer fact that it exists exemplify the differences between the cultural values of the Roman world and those of Christianity. While the culture heroes of the Roman world had always been powerful military commanders and emperors, Christianity promoted heroes who looked very different from the Roman ideal—weak, female, and sometimes even enslaved, like Felicity. The Romans who opposed Christianity as the ultimate enemy of Rome may not have understood the beliefs of the Christians, but they did get something right: the Christian values truly were incompatible with their own.

The story of Perpetua and Felicity allows us to explore the ways the misogyny of Roman society posed difficult questions for women who converted to Christianity and, as a result, for the church at large. Put simply, conversion of women from all ranks of society, from the noble and free to enslaved, challenged Roman culture. The response of the church displayed a willingness to move beyond the confines of traditional Roman culture for women. By defining itself as the family of all believers, the church allowed a life choice of singleness for women that was deeply countercultural. With this life choice came a recognition of women’s worth as powerful prayer warriors and, in the case of women martyrs, faith heroes for all believers.

To understand how revolutionary this was, we must first take a step back and ask: what were the lives of women in the Roman world like?

Perpetua: A Noble Roman Woman

In the mid-fifth century BCE, the Romans passed their earliest law code. Inscribed on twelve bronze tablets, it was creatively called the Twelve Tables. Table V had this to say about women: “Women, even though they are of full age, [because of their levity of mind] shall be under guardianship . . . except Vestal Virgins, who . . . shall be free from guardianship.”

Roman women were supposed to be under the guardianship of a male relative for the entirety of their lives—first their father and then their husband. If a woman was widowed or divorced, she reverted to her father’s guardianship. If the father was deceased, an older brother or another male relative was supposed to take responsibility for her.

As in all other ancient Mediterranean societies, Roman women could not be full citizens. Paradoxically, the main significance of freeborn, legally wed women was that they could give birth to citizens. Indeed, this work of bearing children was expressly mentioned in Roman definition of marriage, and infertility was common cause for divorce among aristocrats. The emperor Augustus, concerned over falling aristocratic birthrates, instituted a law making freeborn women who gave birth to three children exempt from the requirement of guardianship.

Vibia Perpetua was born sometime around 180 CE to a noble family in Roman Carthage. Although it is not clear if her family had Roman citizenship, we can be sure that her upbringing was privileged for its time.

Of course, health threats always loomed. While Roman demography is a tricky science, the estimates that different scholars present are invariably grim. Possibly 50 percent of Roman children did not live to age ten or (a more optimistic estimate) fifteen. Surviving the first year alone was a major milestone in the premodern world, with some estimates suggesting that as many as 35 percent of infants died in the first month, and the more optimistic ones stating the same figure for the first year. But Perpetua defied the odds. She was born around the end of a major pandemic that swept through the empire—the Antonine Plague, which was most likely smallpox. That pandemic, in fact, may have carried off one of her two brothers. One of the visions she describes in her journal is about her brother Dinocrates, who died at age seven and had horrible ulcers on his face at the time of death.

As a noble girl, Perpetua was likely educated at home. Weaving surely was included in the curriculum as the traditional skill for Roman women. Perpetua’s well-composed and thoughtful journal shows that she also received excellent rhetorical education. Women’s literacy in the ancient world was not guaranteed, but an aristocratic woman would have received the best education possible, all with an eye to securing a good marriage.

In her late teens, she was indeed married off, presumably to another local noble, and she gave birth to a son. Yet again she survived a health risk, as did her child. She was well on course to fulfilling her prescribed duties as a Roman matron. But then she discovered Christianity.

By the time she opens her journal, her husband is gone. She never mentions him. Furthermore, she is back to living in her father’s home instead of her husband’s. The most obvious conclusion is that her husband objected to her conversion and considered it a scandal worthy of divorce. Perhaps he even made the argument for keeping her dowry instead of paying it back to her father—a rarity that could only occur if the divorce was demonstrably the wife’s fault.

But Perpetua’s story is not just her own. It is intimately intertwined with that of another young woman who did not leave any writings of her own.

Felicitas: Slave, Christian, Mother, and Martyr

Around the time of Perpetua’s birth, another girl was born and ultimately grew up to be an enslaved woman in Perpetua’s family home in Carthage. Her enslaved name was Felicitas (or Felicity in English). We know much less about her origins. She may have been born into slavery in Carthage or elsewhere in the empire. She may have been one of the many thousands of captives taken during Marcus Aurelius’s military campaigns across the Danube (which concluded in 180 CE) or in another war and sold into slavery in the Roman empire afterward.

Her name, Felicitas, was common for enslaved women. With its associations of fertility, it suggests the possibility that in addition to her expected role as an all-purpose servant in the household, she was also a breeding slave. We know that at some point in her life, she arrived in the home of Perpetua and her family in Carthage. And we know that at some point, like Perpetua, she too discovered Christianity. Did she introduce Perpetua to the faith, or did Perpetua introduce her? Or did someone else introduce them both? We simply do not know.

We do know that Felicity was pregnant at the time of her arrest and that she gave birth in prison the night before her martyrdom. Who fathered this child? Again, we do not know, but Perpetua’s father, as head of the household with absolute power over all in his house, is the most likely contender.

By choosing a martyr’s death, Perpetua and Felicity interrupted the default life story that the Roman Empire had in mind for them. It is worth considering: What might their lives have looked like had they not converted? In the case of Perpetua, she likely would have remained married to her husband or would have remarried, and she would have had more children. Each childbirth would have carried a risk of death for her, but perhaps she would have continued to defy the odds and survive. Since men in Roman society were typically older than women at the time of first marriage, she likely would have been widowed at some point in her thirties or forties. But as an aristocratic woman, she would have had the resources to support herself in old age. If she had born three children, she would have even had that rare luxury—the right to manage her own property without a male guardian.

In the case of Felicity, had she lived, she would have continued in her role as an enslaved servant and possibly breeder, giving birth to additional children who would have inherited her enslaved status. Unlike the slaveholders of the American South, Romans did not often sell slaves born in the house. So at least she would have been able to see her children grow up—assuming, of course, that they survived infancy and childhood. Once she turned thirty years of age, she would have been eligible for manumission. In that best-case scenario, and especially if she had particular skills, she could have either started on a business venture of her own or assisted her former masters in some way. In the worst-case scenario, if she were freed because she had outlived her usefulness to the household, her status in society would have been akin to the most insecure category of all free persons in the empire—childless widows.

Uncomfortable Questions

Perpetua’s journal raises a number of challenging and uncomfortable questions. At the most obvious level, her repeated disobedience to her father and the state authorities challenged both Roman law and various commands in the New Testament. By refusing to renounce Christ, Perpetua disobeyed three different men with authority over her: her husband, her father, and the representatives of the Roman state. A male convert in her position would only have been guilty of disobedience to the state.

The hints of possible sin in Perpetua’s journal extend further. The anonymous editor was clearly worried that her lack of discussion of her husband could lead to assumptions of sexual immorality by the readers. The editor’s introduction notes that Perpetua had been legally wed, but Perpetua herself never mentions this husband. The editor seems concerned that a woman who so easily disobeys all authority figures in the matter of her faith would be judged harshly by the readers.

Looming over the entire narrative is the uncomfortable question of Perpetua’s abrogation of her responsibilities as a mother. By choosing to die in martyrdom, she leaves her son to be raised by her parents.

Felicity’s conduct is even more shocking: according to the editor, she prayed before the execution that she would give birth in time. Pregnant women could not be executed, and she did not want to delay the execution. When she gave birth the day before the games, she felt that her prayers were granted—even though that meant she had to give up her newborn baby less than twenty-four hours after birth.

The vast majority of martyrdom accounts before Perpetua told of the martyrdom of men. It appears that even Perpetua herself realized that her identity as a woman, therefore, impacted the expected narrative. Why did she write this journal, and what did it accomplish?

The Church’s Response

Perpetua’s journal was published, but the story does not end there. Over the next half century, Carthage was the site of publication of multiple treatises on women’s dress and behavior. Modern scholars have been quick to attribute these texts to the misogyny of individuals like Tertullian, but I think that they show, rather, the church’s desire to recognize women’s unique struggles in Roman society and, as a result, within the church. In this regard, it is not an exaggeration to see these texts as the church’s response to Perpetua.

Tertullian published two treatises on women’s clothing, On the Veiling of Virgins and On the Dress of Women, and a related treatise On Modesty. He also wrote two books on marriage, which address women’s issues as well: On Monogamy and To His Wife. His biggest fan and intellectual successor, Cyprian, who would serve as bishop of Carthage from 248/9 to 258 CE, would go on to write a treatise On the Dress of Virgins. This body of literature, new to the church, aimed to address the kinds of challenges that were unique to women in Roman society, which were carried into the church.

This body of work, taken as a whole, consistently displays a language of provision and care. Replacing traditional Roman guardianship, the church becomes understood as the parent of women converts, whether young or old, married or single. These treatises acknowledge Perpetua and Felicity’s greatest challenge: women in the Roman world had no right over their own bodies, much less any significant life decisions. Clothing, in particular, served to mark women’s social class in a way that reflected on their families. The sin of disobedience to their Roman guardians and government authorities, of which women converts were guilty by default, would be erased or at least mitigated through the church’s intersession as their new family. Clothing was simply the surface level at which this care was manifested.

Through denouncing ostentatious Roman dress, Tertullian and Cyprian provided women converts a freedom to depart from the Roman expectations of them, which included strict standards regulating appearance, the requirement to get married and have children, and the requirement to worship the Roman gods. Christians were the first group in the history of the world to value women of all life choices and circumstances, whether single, married with children, married and childless, or widowed.

The acknowledgement of singleness as a viable option allowed the church to value women for more than simply their childbearing. Furthermore, the uniform standards of dress helped to erase social categories, encouraging the equality of believers in the church, just as we see modeled by Perpetua and Felicity, a noblewoman and her slave, who were martyred together as equals. More generally, the proclamation of universal moral standards encouraged the recognition of both men and women’s moral agency and their shared responsibility to seek the good.

In the church, a revolutionary type of equality was afoot—one that would reverberate through the centuries and shape our understanding of human dignity for millennia to come.

Taken from Cultural Christians in the Early Church by Nadya Williams. Copyright © 2023 by Nadya Williams. Used by permission of Zondervan.

www.harpercollinschristian.com