The arrival of relatively effective birth control in the 1960s changed the women’s movement overnight. Suddenly, it seemed possible that instead of having to grapple with women’s sex-specific vulnerabilities—fertility, pregnancy, caring obligations—women might campaign for the right to control or even evade these altogether. Anything more fleshy, dimorphic, or even faintly redolent of “stereotype” has since been largely memory-holed. Pop-feminist orthodoxy now holds that “womanhood” has nothing to do with reproduction, and feminism is about liberation for everyone.

If this is your worldview, you’ll most likely praise pre-1960s feminists to the extent that their work aligns with this program, and either ignore or critique those ways it does not. More recently, though, a new wave of feminist heretics has set out to recover what has been memory-holed. It’s a rich field: much of first-wave feminism is profoundly embodied, often strongly pro-life, and very difficult to classify according to the Manichean poles of twenty-first-century culture wars.

Yet this renewed curiosity about our feminist foremothers is not conservatism, exactly. Rather, it is the recovery of a feminist counter-narrative long obscured by the orthodox myth of liberal progress. Many of today’s heretics, myself included, arrived at our wrongthink by leaning as hard as possible into liberal feminism, only to come out the other side with a renewed appreciation for our female bodies, and for freedom’s practical limits. Here, too, our rebellion has a first-wave antecedent: a woman who delved so vigorously into the nascent liberal feminist project that she ended up somewhere paradoxically reactionary. That woman is the writer and hydropath Mary Gove Nichols (1810-1884).

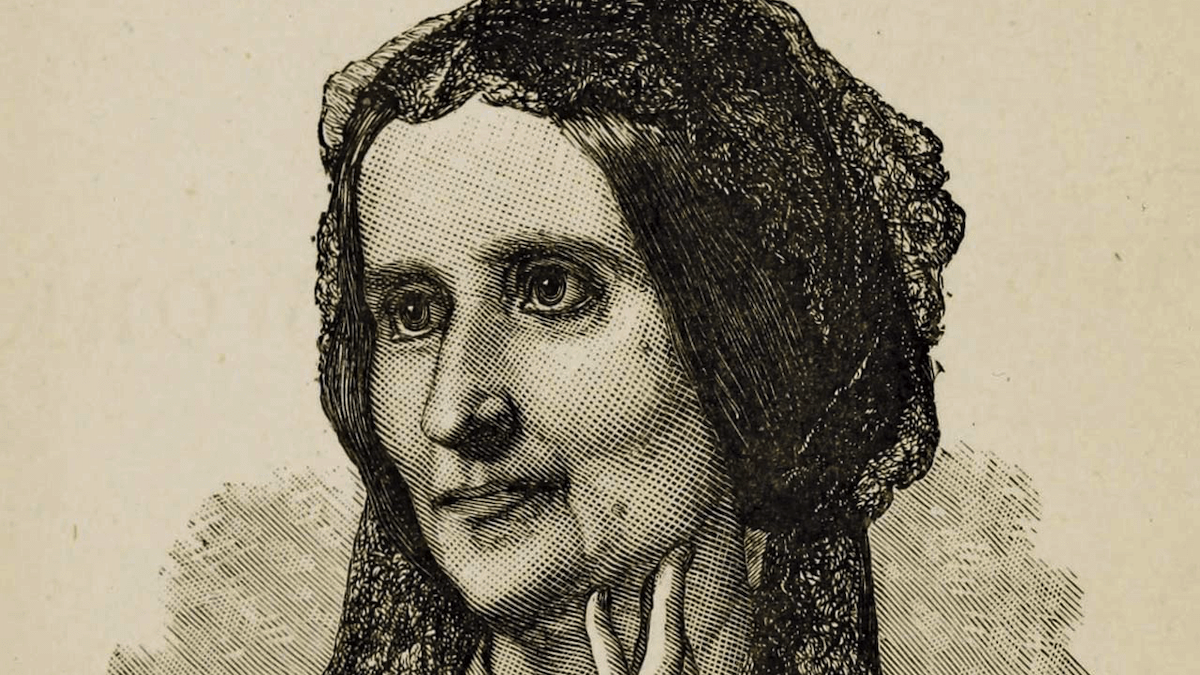

Though she is little-known today, Mary had a hand in a great many radical movements of her day, from women’s health and education to spiritualism. Her work anticipated key issues in feminism. Though she wouldn’t have described herself as a women’s rights activist, she dedicated her life’s work to women’s education and health. The course of her life, and the challenges she faced, vividly illustrates why the nineteenth-century women’s movement came into being. A prolific speaker, writer, and entrepreneur, in her younger years she argued for “free love” and against coverture marriage, advocating the right to divorce at will. She spoke for education in women’s health, railed against women’s restrictive clothing, and blazed a trail for female professional achievement and participation in public life.

Yet her pursuit of new spiritual utopias ultimately led to her embrace of religious tradition, and her advocacy for sexual emancipation culminated in a heartfelt defence of chastity. And early, bitter experience of miserable subjection to a man she loathed ended, most surprisingly of all, in her call not for war between the sexes but solidarity.

In short: over one prescient lifetime, Mary Gove Nichols speed-ran the narrative arc of liberal feminism, from emergence in the crucible of industrialisation, to an ecstasy of individual freedom, followed by a long slow collision with reality. The eventual synthesis that emerged in her writings between legitimate calls for emancipation, advocacy for self-discipline, and solidarity between the sexes anticipates by almost a century and a half those contemporary women now seeking a synthesis between the positive achievements of feminism and the pragmatic realities of our sexed life in common.

Youthful Fear of Bonds

Mary’s New Hampshire birth, childhood, and maturation straddled America’s transition from agrarian beginnings to industrial might. Her childhood home was a model of the agrarian economy Jefferson inherited. Her adulthood, by contrast, was spent among a largely urban bourgeoisie increasingly liberated from agrarian labor by industrialization. And the course of her disastrous first marriage illustrates the predicament this rapid change imposed on women.

In America, as in other nations, industrialization drained work from homesteads into offices and factories, which reduced women’s productive contribution to households—and, with it, their economic and political agency. The women who once worked alongside men in a “productive household” became principal consumers and educators of children, in the “separate sphere” of bourgeois domesticity.

Women happily married to virtuous men could flourish under this order, and periodicals such as Godey’s Lady’s Book were full of articles written by such women. Yet this legal, political, and cultural environment saw married women as “one flesh” with their husband, meaning that they had no separate legal or economic rights, which spelled disaster for any woman married to a spendthrift, abuser, or drunkard.

This was Mary’s predicament. At 22, she was pressured at into an ill-advised marriage to Hiram Gove, a Quaker hatmaker eleven years her senior. She described him later as a man “incapable of self-governance” who nonetheless “arrogated the rule over my soul and body, with the utmost confidence.” Gove was a suffocatingly controlling presence, reading all her letters, and forbidding her to leave the house without his permission. As she later recounted,

I was enjoined to “love, honor, and obey” a man who was mean enough to require all this. I could obey him, and I did, nearly to the stultification of all my powers, mental and material. But what woman, who is worthy the name, can love or honor disease, stupidity, and a blind arrogance of authority/ yet the Church and the World said this man’s will was to be my law.

Mary’s one ray of hope, paradoxically, was that Hiram was a hopeless breadwinner. Instead, he made her do it all: not only housework and caring for their baby, but also earning money by teaching, writing essays, poems, and fiction for publication. Eventually, in 1837, she embarked on a convention-defying series of public lectures on anatomy.

New England’s rapidly urbanizing bourgeoisie was a ferment of intellectual curiosity and lifestyle experimentation. Public lectures were the rock concerts of the age, and Mary soon became a rock star. Her wildly popular lectures ranged across factual content and social commentary, enjoining women to improve their health and wellbeing through self-knowledge, right living, and the avoidance of masturbation. In particular, she singled out the pernicious effects of tight lacing, often in terms with a clear subtext of lament at the tightness of her own constraints:

O that the customs of society would let females out of prison. O that they might be allowed to rid themselves of the torment and torture of a style of dress fit only for Egyptian mummies. And will our country women ever be such servile slaves to customs they might reform? Will they always ape the wasp, when the freedom of grace and ease are within their reach?

Buoyed by professional success, in 1841, Mary finally cut her own lacing off. She left Hiram’s house and moved back to her parents’ home with baby Elma.

Yet even then, Hiram’s hold over her remained. Divorce could not be initiated by a woman, nor did Mary have any right to keep Elma from customary paternal custody. When, in 1844, Hiram reclaimed his daughter (against Elma’s own wishes), Mary resorted to kidnapping in order to regain care of her child. By the law of coverture, Hiram even owned the copyright to her first book: the 1842 Lectures to Ladies on Anatomy and Physiology. Mary chafed at the injustice of her inability to hold the title to her own work, and she sought in vain for a means of escaping this bind.

In this light, we can well understand her writings against marriage—at least, against marriage following the legal paradigm of her era. And perhaps we can understand her terror of restriction, which she described in her 1855 autobiography as a “holy fear” of “bonds.”

Embracing Passion, Discovering Freedom’s Limits

Yet Mary was not the kind of woman to let her life be shaped by fear, any more than by social custom. Because medical training was still closed to women until the 1850s, Mary studied the alternative health practice of hydropathy, or “water-cure.” By 1844, she was practicing water-cure in New York City, amid a circle of artists, poets, philosophers, spiritualists, health reformers, and political idealists.

There, she met and fell in love with Thomas Low Nichols (1815-1901), a journalist who shared her interest in Fourierism, a form of utopian proto-socialism that envisaged communities ordered only by “passional attraction.” And in the attraction that swiftly blossomed between Mary and Thomas, everything was different. Where Hiram ignored or censored Mary’s writing, Thomas told her “You must write.” Where Hiram grudgingly allowed her to work, while living off her earnings, Thomas told her: “Follow your profession; it is noble, useful, honorable, and will command the world’s respect.”

When Hiram finally divorced her to marry someone else, Thomas’ proposal honored Mary’s autonomy in every way Hiram had not. In her autobiography, she describes the demands with which she sought to shield her hard-won freedom:

In a marriage with you, I resign no right of my soul. I enter into no compact to be faithful to you. I only promise to be faithful to the deepest love of my heart. … I must keep my name – the name I have made for myself, through labour and suffering … I must have my room, into which none can come, but because I wish it.

Thomas agreed to every stricture. In 1848, they were married.

In the 36 years of loving marriage and close collaboration that followed, Mary founded, experimented, and created. She wore bloomers, explored mediumship and her capacity for spirit healing, and wrote prolifically. And from the vantage-point of her blissful second marriage, she and Thomas became leading figures in the “free love” or anti-marriage movement. This should not be confused with the “free love” movement that emerged from the sexual revolution, which presupposed the existence of reliable contraception. Rather than advocating promiscuity for both sexes, the earlier movement sought to disaggregate sexual desire from legal and political ties and to counter the then-common perception of women as purely receptive, sexless beings. To that end, Mary and Thomas co-wrote a book-length critique of marriage in 1854 that called for the right to divorce, and for both sexes’ right to sexual freedom and pleasure.

Her life and work alike anticipated flagship feminist issues to come: the right to divorce, to a separate identity, to an independent professional name. She fought for the right to the resource made famous nearly a century later by Virginia Woolf: a room of one’s own. Crucially, she challenged the then-common belief that women experience no sexual desire, arguing in Marriage that “the apathy of the sexual instinct in woman” was caused by having “no right to herself if she is married.”

A “healthy and loving woman,” she insisted, “is impelled to material [sexual] union as surely, often as strongly, as man.” In contrast, loveless marriage results in “exhausted and diseased nerves,” and sickly children born in pain and struggle. She even—scandalously for the age—approvingly recounted the story of a woman who endured years of loveless marital rape, before conceiving a child in a passionate extramarital affair.

In calling on women to prioritize affinity and sexual desire, Mary anticipated by over a century Germaine Greer’s call for women to reject what Greer saw as the “castrated” life of a housewife, for a “deliberately promiscuous” one filled with the ‘dignity, integrity, nobility, passion, pride that constitute personhood.” But as Mary threw herself into the pursuit of freedom from blind convention, she also began to push at freedom’s limits.

By 1855, when Mary and Thomas embarked on their most ambitious project yet—the utopian “Memnonia” community in Yellow Springs, Ohio—she viewed “individual sovereignty” as something that should be qualified by willingness to submit to human authority in pursuit of the good life. Promotional literature for Memnonia explained that the community’s leader would exercise “a despotism, as wise and benevolent as circumstances will admit.” And if her earlier emphasis on individual freedom was increasingly tempered by an acknowledgement of the social necessity of hierarchies of power, so too “free love” was to be balanced—if not by state institutions, but at least by self-restraint. Sex, she concluded, should only be procreative: “Material Union is only to be had, when the wisdom of the Harmony demands a child.” In this way, a nominal “free love” that was in practice the “purer chastity of a higher law” would deliver “The law of Progression in Harmony.”

None of this was enough to dispel the rumors of sexual excess. Horace Mann, president of Yellow Springs’ Antioch College, denounced the Nicholses’ project as “the superfoetation of diabolism upon polygamy,” whipping up such local hostility that Memnonia never thrived. It disbanded in 1857 after just two years.

Conversion and Synthesis

My own about-turn from full-throated progressivism was triggered by the failure of a start-up into which I’d thrown my whole being. Mary’s was, too. Her transformation was even more startling than mine: after Memnonia collapsed in 1857, during one of Mary’s regular séances, she encountered a spirit claiming to be St. Ignatius Loyola, who instructed her in Catholic doctrine. This encounter would prove the beginning of her conversion to Roman Catholicism.

She remained an observant Catholic until her death in 1884. And the synthesis Mary arrived at—the harmonizing of her early calls for a life guided by “passional attraction” and her later embrace of the Catholic understanding of natural law ordained by God—can be seen in her 1869 call to both sexes for emancipation through “a life of marital chastity” within a marriage characterized by “the blessed strength of a spiritual love,” in which men and women ennoble one another:

Woman would live chastely, lovingly, in holiness and health, if she could have the blessed strength of a spiritual love to sustain her. What is wanted now for the world’s redemption is wisdom and self-restraint in man. Only as he comes to a loving and living and chaste unity with woman, can either be saved for this world.

Mary is by no means the last feminist intellectual to have found spiritual and intellectual riches in Catholicism—a doctrine that informs the work of numerous feminist thinkers featured regularly in these pages. Some of these, such as Abigail Favale, experienced almost as dramatic a conversion as Mary. Though I’m not among the converted, many of these women started out—as I did, and as Mary did, more than a century before us—fully on board with the liberal project, before seeking their own synthesis with tradition.

For Mary Gove Nichols, all her most hard-won discoveries emerged from just such a difficult synthesis. Through a lifelong defence of “passional attraction,” she concluded that there’s a place within the women’s movement for sexual illiberation. That is, she called for a recognition that sexual restraint is a prosocial force: “the fertile soil which produces the highest beauty.”

While she never wavered in denouncing as “despotism” the notion that husbands possessed any “marital right” to insist on sex against their wife’s consent, her proposed cure was no longer to abolish marriage, as she had argued during her “free love” campaigns. Now, she sought to align her longstanding advocacy for mutually respectful, embodied intimacy with her Roman Catholic faith, by seeking not to dissolve the institution of marriage but to discipline and ennoble it for both sexes—the same cause recently championed by Erika Bachiochi. Mary also prefigured my own call for a feminist solidarity with men, rejecting the contemporary notion of mutual hostility between the sexes and calling instead for interdependence, in terms that presciently anticipate the bleak contemporary stand-off of the modern “sexual marketplace”:

It is a great mistake to consider man and woman as antagonists, as having irreconcilable interests – like buyers and sellers, each trying to gain an advantage over the other. The interests of male and female … are as indissoluble as if they formed one soul and one body. Man cannot … restrain woman from the exercise of her highest freedom [without] bringing misery to himself by bringing disorder and death to her and her offspring.

Was Mary Gove Nichols just an early liberal, unfortunately cramped by the constraints of her age? In her fearless life, and prolific, passionate words, we find a microcosm of the challenges posed to women by the cultural, legal, and economic convulsions industrialization wrought. These changes transformed family life, often to women’s detriment, and impelled the emergence of the women’s movement as women sought to remedy these injustices.

But if Mary’s struggles against domestic abuse, professional stricture, and public censure underline that movement’s legitimacy, so her eventual turn to faith and calls for chastity and solidarity between the sexes have proven prophetic of its inherent tensions. Her life and work anticipated much of the arc of liberal feminism, and her pursuit of freedom led her to conclusions that challenge some of the movement’s most cherished modern orthodoxies. In her effort to forge a new synthesis from these paradoxes, then, I see a prophetic harbinger of the newest turn in feminism’s 250-year dialectic. I see, in fact, feminist prehistory’s most avant-garde reactionary.